|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

International Record Review, March 2013 |

| Roger Pines |

|

|

|

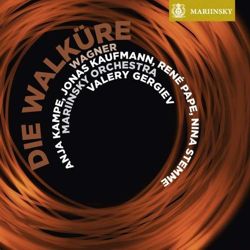

Wagner - Die Walküre |

|

Valery

Gergiev, artistic director of the Mariinsky Theatre, has apparently

concluded that, in documenting his company's Walküre, international

Wagnerian stars would be required for the leading roles. Only the

supporting parts — Hunding, Fricka and the Valkyries — are filled here by

Russians. Valery

Gergiev, artistic director of the Mariinsky Theatre, has apparently

concluded that, in documenting his company's Walküre, international

Wagnerian stars would be required for the leading roles. Only the

supporting parts — Hunding, Fricka and the Valkyries — are filled here by

Russians.

This show belongs to Jonas Kaufmann (Siegmund), whose

bronzed timbre is deeply satisfying whether in heroic or intimate utterance.

His legato is immaculate, with many phrases taken in a single span where

other tenors would be grabbing extra breaths. When genuine forcefulness is

crucial, as at the end of Act 1, Kaufmann sings as thrillingly as any

Siegmund since Jon Vickers, yet his poetic qualities are also on a par with

those of his great Canadian predecessor's level (as in a flawless

'Winterstürme'). Kaufmann's singing in the 'Todesverkündigung' is

as

nobly phrased as one could desire. His expertise as a Lieder singer tells in

his detailed expressiveness throughout this portrayal, limning a thoroughly

persuasive portrait of the resolute, courageous, deeply sensitive Wälsung.

Here is surely the most moving and beautifully sung Siegmund on disc since

Vickers's 1961 performance under Leinsdorf.

Kaufmann's Sieglinde,

Anja Kampe, is frustrating. The voice boasts an exceptionally rich-toned

bottom octave, but a serious loss of colour on top gives constant cause for

worry. Kampe's vocal acting gives us an unfailingly sincere Sieglinde, if

not an especially individual one. Partnering the soprano and tenor in Act 1

is the Hunding of Mikhail Petrenko, satisfactory but rather young-sounding

in this forbidding role and somewhat grainy of voice.

Rene Pape

(Wotan) is, of course, a bass, and he doesn't sail into the easy upper

extension boasted by bass-baritones George London and Hans Hotter in their

prime. Most of the big-scale top notes (beginning in his very first speech

with the leap to high F sharp on 'reite zur Wal') are effortfully produced.

Pape's ease at the bottom generally compensates, and there are numerous

inward-looking moments that impress: much of the monologue (exceedingly

intelligently presented overall) and certainly 'küßt er die Gottheit von

dir', with Wagner's ppp marking memorably observed. The god's tenderness is

perceptible, and one clearly senses his pain in the final dialogue with his

daughter. I do miss the sheer majesty of Wotan — Pape's is a comparatively

lightweight instrument for this music —but at 'In festen Schlaf' and,

indeed, in all the quieter portions of the role, one does hear the singer at

his best.

Brünnhilde is the vocally fearless Nina Stemme, who has

even the trills of 'Hojotoho!' in hand. She and Kampe — each an utterly

direct, unfailingly sympathetic vocal personality — also share an

extraordinary darkness of tone (contraltos would kill for the luscious

richness of Stemme's lower register in 'War es so schmählich'). Unlike her

colleague, Stemme can navigate

above the stave with no sacrifice in

tonal body. Some excess vibrato (the only passing weakness in Stemme's

technique) can intrude, and the very thickness of the sound impedes clear

enunciation here and there. Still, one should be exceedingly grateful

for the Swedish soprano's terrific confidence and consistent beauty of

voice. She saves the best for last —the

character's final speech is

truly heroic and deeply stirring.

Ekaterina Gubanova brings luscious,

Ludwig-like vocal velvet to Fricka, presenting a notably dignified and

womanly goddess, eschewing both ranting and shrewishness. She sings rather

better German than her compatriots heard as the Valkyries, who manage to

fill the bill vocally in their ensembles. Individually strongest of the

sopranos is Irina Vasilieva's Ortlinde, and Ekaterina Sergeeva's Siegrune

does best among the mezzos (although she errs in her text, singing 'Hort'

instead of 'Hort').

Technically the Mariinsky orchestral players have

no problems at all, and Gergiev's great achievement is to draw consistently

lovely tone from them through the entire performance. One can't deny the

pleasure derived from such well-shaped playing, but Act 1 and much of Act 2

sounds like a read-through. In the prelude one longs for the bite and slash

in the strings that

makes Keilberth at Bayreuth so memorable. Repeatedly

in Act 1 specificity of expression is minimal, with Gergiev seeming oddly

distanced from the piece (it's the singers exclusively, not the conductor,

who supply the passion here).

In Act 2 the Fricka scene inspires

little excitement from the pit. More effective (if not quite offering the

magnificence one hopes for in this passage) is the interlude before the

Wälsungs' entrance, and Gergiev does collaborate satisfactorily with Kampe

in Sieglinde's hallucination scene. The 'Todesverkündingung' also goes quite

well musically and dramatically, seemingly catching Gergiev's imagination

more than what we've heard so far.

The orchestra's virtuosity is

rewarding in the 'Walkürenritt' and as Act 3 proceeds we finally feel

Gergiev consistently connecting with the drama. Unlike many conductors these

days who

rush insensitively through Brünnhilde's glorious 'Fort den

eile', Gergiev allows Stemme to phrase this passage with sufficient breadth.

The conductor offers both his Brünnhilde and Wotan

good support in their

final confrontation. Gergiev loses the excitement to a degree in the opening

portion of the 'Abschied'. The interlude before 'Der Augen leuchtendes Paar'

is strong, not so the 'Feuerzauber'.

The recorded sound is excellent.

Mariinsky's booklet contains the libretto, translation, biographies, a

few paragraphs on Wagner's life and a brief but splendid introduction to the

opera itself. Ring enthusiasts will want to hear Pape, Stemme and especially

Kaufmann, but —despite the large number of new Walküre recordings to have

entered the catalogue in the past decade — my top choices remain the

Bayreuth performances led by Bohm (1967) and Keilberth (1955).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|