|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Musicweb International |

| Simon Thompson |

|

|

|

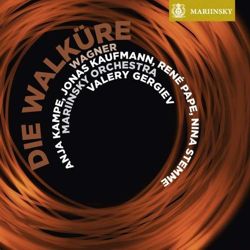

Die Walküre, Recording of the Month |

|

|

This

is the first major release of the Wagner bicentenary year to come my way,

and it’s thrilling. Even more exciting is the news that it is only the first

instalment of a complete Mariinsky Ring: Rheingold will follow in September

2013, with Siegfried and Götterdämmerung in 2014. If this instalment is

anything to go by then this it’s going to be a Ring to cherish. This

is the first major release of the Wagner bicentenary year to come my way,

and it’s thrilling. Even more exciting is the news that it is only the first

instalment of a complete Mariinsky Ring: Rheingold will follow in September

2013, with Siegfried and Götterdämmerung in 2014. If this instalment is

anything to go by then this it’s going to be a Ring to cherish.

So much about this set works so well, but it makes sense to begin

with the singing. Much of the attention this release gets will focus on

Jonas Kaufmann’s Siegmund, and rightly so because he is a marvel. He is now

at the point of his career where his voice is perfect for the role of the

Wälsung hero. He combines lyrical beauty with dark, rugged heroism and a

supreme sense of excitement in articulating every phrase. The baritonal

darkness of his voice makes you sit up and take notice from the very first

phrase, and it’s this that makes his assumption of the role so distinctive.

It adds an even greater layer of pathos to the character’s suffering while

giving Siegmund extra heroic grandeur that makes us root for him all the

more. The excitement is there in his cries of Wälse! Wälse! and in his

ringing excitement of Wälsungen-Blut that brings down the curtain on Act 1,

but the lyrical beauty of his Winterstürme is every bit as compelling, as is

his lovely song to the sleeping Sieglinde at the end of Act 2. As important

as the vocal beauty, though, is the thoughtful artistry that underpins

everything he does. Like a lieder singer, he seems to have thought deeply

about the text and each phrase feels laden with meaning, articulated with

clarity and precision. Listen, for example, to the way in which he grows

into his narration of his past in the first act. The opening phrases seem

tentative, even nervous, as if he is reluctant to share his life story with

Hunding, but the monologue grows like a great arch leading to a final

couplet (Nun weisst du, fragende Frau...) that will break your heart.

Likewise, the entire Todesverkundigung scene grows in stature from its

dream-like beginnings through to a hair-raising finale, electrified by

Kaufmann’s identification with the text, before subsiding into the peace of

Zauberfest. Kaufmann’s Siegmund is more lyrical than Jon Vickers (Karajan on

DG), more beautiful than Gary Lakes (Levine on DG), more distinctive than

Poul Elming (Barenboim on Warner) and more heroic than James King (Solti on

Decca or Böhm on Philips). The closest comparison I’ve come across on disc

is with Ramón Vinay (Krauss on Archipel and Keilberth on Testament) whose

dark voice is of a similar hue to Kaufmann’s and who has a similarly

complete identification with the character. This should be enough to show

you that Kaufmann’s Siegmund is in a very special league indeed, and for his

contribution alone this set is worth the purchase price.

This is far from being a one-man show, though, because the rest of the cast

are just as notable. Anja Kampe’s Sieglinde develops most movingly as the

opera progresses. When she first appears in Act 1 her primary characteristic

is of clarity and thrilling nobility, as well as beauty of tone that you can

take as read. Her attempt to get Siegmund to remain in the house of bad luck

(So bleibe hier!) made the hairs on my neck prickle, and she crests the wave

of ecstasy in Du bist der Lenz. However, by the time of Acts 2 and 3 she has

assumed an air of wounded vulnerability, almost broken in Act 3 when she

asks to be left alone. She revives rapidly when she hears the news of her

child, though you’ll hear O herrstes Wunder sung better from other sopranos.

René Pape’s Wotan is almost as remarkable as Kaufmann’s Siegmund. He has

already recorded roles like Landgrave Herman and King Heinrich for

Barenboim, and his graduation into Wagner’s most difficult role is a

triumph. He has a bewitching beauty of tone that will win over any listener,

but his secret weapon is the way he sings with a bel canto-like ear for the

long line. This obviously helps to make the farewell very moving, but it

also helps to energise and unify other moments that can sprawl, most notably

the great monologue of Act 2 which ebbs and flows with a natural air that

you seldom hear from other singers. His interpretation emphasises the warmth

of Wotan the father, and during the moment in Act 3 where he pronounces his

sentence on Brünnhilde you can really sense the character’s pain, as if he

is forcing himself to say the reluctant words. As that errant daughter, Nina

Stemme reminds us that she is the premier Wagnerian soprano at work today.

Her voice has a grandeur and nobility that lends dignity and stature to the

role of the Valkyrie - it is another reason why the Todesverkundigung is so

thrilling, as is her interaction with her sisters at the start of Act 3 -

and her singing with Pape makes the end of Act 3 very special. She still

manages an element of impetuosity in her Hojotohos that open Act 2, even if

she never sounds exactly girlish. Mikhail Petrenko is a genuinely malevolent

Hunding. He never falls back on posturing or vocal colour alone, but uses an

edge to his voice to make him sound properly sinister while remaining

exciting at the same time. Ekaterina Gubanova’s Fricka is noble, dignified

and very well sung, if slightly anonymous in her vocal acting. Furthermore,

I have seldom heard a band of Valkyries sound so convincingly war-like. They

sing thrillingly, but have an excited ring about their voice that never lets

you forget that these are warrior maidens.

Gergiev’s Wagner has not

always been well received - his Ring was slated during its appearances in

this country - but for me this recording shows him as a Wagnerian of

importance and skill. He conducts with an eye on the long view. This works

exceptionally well in Act 1, whose orgasmic climax on the retrieval of the

sword is so powerful because it has been so well prepared. The same is true

for Act 3, which unfolds entirely appropriately, each scene giving way

naturally to the next, though for me it was marred by a too speedy rendition

of the Magic Fire Music which made the end of the act feel rushed. Only Act

2 felt a bit episodic, though it’s sometimes hard to make it seem anything

else. He is particularly skilled at judging transitions, and in most cases

they are so powerful because you barely notice them, a skill surely honed

from his vast experience in the theatre. His tempi don’t tend to draw

attention to themselves, though a few times I noticed him holding onto a

moment for a fraction longer than you might expect (such as in Siegmund’s

Wälse monologue), thereby heightening the expectation for what is to come

next. He repeatedly lights up a particular passage with a sharp flash of

colour, and in this he is helped by the superb playing of the Mariinsky

orchestra. The press notes for this release make great play of the theatre’s

connection with Wagner, including the informed speculation that it was this

orchestra that first played any music from The Ring, and their playing is

indeed very special, comfortably passing any comparison test with orchestras

to their west. The surging, pulsing strings are particularly effective in

Act 1, and the brass add a special touch of class to the climaxes of Acts 2

and 3. The whole enterprise is supported by excellent recorded sound. The

engineers have done a fantastic job of capturing the performances (sessions

and live concerts) with supreme clarity and, perhaps surprisingly, they

reveal an enormous amount in the Ride of the Valkyries, laying bare the

sound with a degree of clarity that is often lost elsewhere: you’ll never

hear better piccolos in the Ride than here!

Few operas take their

audience on a journey as extensive or profound as does Walküre, and it is

difficult for any recording to do it complete justice. In terms of modern

performances, though, this is the finest CD version to have appeared in many

long years. For me, this version surpasses digital recordings from Haitink,

Levine and Janowski, and, while it won’t make anyone throw away Solti,

Keilberth or (especially) Böhm, it is able to look them in the face and

stand the comparison. The booklet contains a thoughtful essay with libretto

in Russian, German and English. Incidentally, while some of the music was

recorded live in concert, there are no intrusive audience noises, though you

might pick up a fair amount of groaning in the quieter passages, presumably

coming from the maestro himself.

If the rest of the Wagner

bicentennial produces recordings as good as this then we are in for a great

year. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|