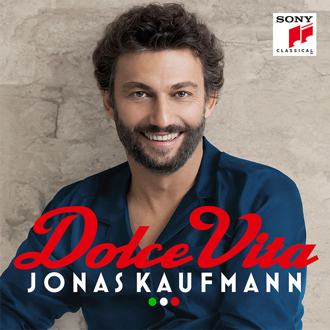

It

is hardly surprising with Christmas on the way that the world’s

premier tenor should release a crowd-pleasing album bursting

with winter sunshine. The Vespa-blue themed digipackaging is

handsomely produced with the full Italian texts translated into

three languages, far too many brooding photographs of our

dreamy, handsome, photogenic singer and an inside spread of the

Trevi Fountain to put us in the mood for an anthology of

favourite Italian songs dating back to 1881 (Gastaldon’s “Musica

proibita”), through the great era of Neapolitan ballads to

crossover hits of the post-war decades up to “Il canto”, written

for Pavarotti in 2003. For good measure, we have - in German,

and English and French but, interestingly and ironically, not in

Italian - a thoroughly irritating and self-consciously jokey

essay, which is short on actual information and very long on

whimsy, by one “Bodo Rossi”, which looks suspiciously like a

pseudonym to me – although I am open to correction on that one.

The author never spoke a truer word than when he concludes his

notes with the sentence, “And I’m already in irritatingly high

spirits.” It

is hardly surprising with Christmas on the way that the world’s

premier tenor should release a crowd-pleasing album bursting

with winter sunshine. The Vespa-blue themed digipackaging is

handsomely produced with the full Italian texts translated into

three languages, far too many brooding photographs of our

dreamy, handsome, photogenic singer and an inside spread of the

Trevi Fountain to put us in the mood for an anthology of

favourite Italian songs dating back to 1881 (Gastaldon’s “Musica

proibita”), through the great era of Neapolitan ballads to

crossover hits of the post-war decades up to “Il canto”, written

for Pavarotti in 2003. For good measure, we have - in German,

and English and French but, interestingly and ironically, not in

Italian - a thoroughly irritating and self-consciously jokey

essay, which is short on actual information and very long on

whimsy, by one “Bodo Rossi”, which looks suspiciously like a

pseudonym to me – although I am open to correction on that one.

The author never spoke a truer word than when he concludes his

notes with the sentence, “And I’m already in irritatingly high

spirits.”

Whatever I say, this CD will sell well – and I

talk as a great Kaufmann fan, but when he is in the right Fach.

No great tenor ever scorned these songs; indeed Caruso’s

gramophone sales were enormously bolstered by them. Gigli, Di

Stefano, Corelli, Del Monaco, Pavarotti, Carreras in his brief,

youthful prime and, very recently, Juan Diego Flórez all

recorded and sang them in concert con gusto and con amore, but

you notice what they have in common? Yes; they are all Latin

tenors with bright, sunny voices capable of a pure, honeyed

tone, and none of them sang Tristan, as Kaufmann is about to do.

His big, burly, baritonal tenor is hardly the right vehicle for

this repertoire; the sound is often quite raw and rough, nearly

always with a suggestion of break between the registers, as in

the repeated top As of “l’ebrezza dell’amor” in “Musica

proibita”, where Kaufmann is too effortful in comparison with

Caruso or Carreras. He also employs a constant “coup de glotte”

attack which breaks the line and legato, and throwing in

concluding B flats is not always the most musical option.

Corelli is guilty of the same excess; Di Stefano and Del Monaco

prefer the less showy but more apt top A as the climax to “Torna

a Surriento”, but if you are going to conclude with a top B

flourish, then Corelli’s is actually more sensuous and

thrilling, while Di Stefano is brings more rhythmic impulse to

the song, where Kaufmann is rather staid and detached.

It

does not help that the orchestral arrangements are really

overblown and played coarsely by a less than refined Palermo

band. “Core ‘ngrato” is murdered both in terms of the stentorian

singing and the instrumentational embellishments. Corelli’s

album, recorded in the early 60’s, is similarly blighted – or

enhanced, depending on your taste – with swooning, Mantovani

strings, but at least there we are spared the souping up effect

of glissandi horns, flutes and violins, which really do

constitute overkill. Surely a gentler, simpler more seductive

approach of the kind Caruso, Di Stefano and Corelli provide is

required for this gorgeous lament. Interestingly, Kaufmann is

one of the few to sing the complete four-stanza version

including the advice from the Father Confessor to steer well

clear of Catari. Caruso also sings a fuller version but with a

more sanitised text.

Not every song here has pretensions

to being an “art song”, nor need it have. Nonetheless, the more

recent numbers surely benefit from a sweeter, cleaner tone of

the kind Pavarotti brought to them; this listener is often

conscious of hearing a big, Wagnerian tenor crooning to rather

charmless effect and, for all Kaufmann’s proficiency in the

language, an absence of real Italianità.

|