|

THE FESTIVAL'S NEW PRODUCTION THIS YEAR, Lohengrin, is enough to challenge

even a seasoned reviewer, let alone anyone unfortunate enough to come to

this opera for the first time. As with Herheim's Parsifal, there were two

narratives working concurrently, one dystopian, the other erotic, but in

this case we were subjected to the whims of a German director determined to

sew controversy. The 69-year-old Hans Neuenfels is perhaps most famous for

incorporating roast chickens into his Aida and for using Mohammed's head in

Idomeneo, which caused a storm of protest. THE FESTIVAL'S NEW PRODUCTION THIS YEAR, Lohengrin, is enough to challenge

even a seasoned reviewer, let alone anyone unfortunate enough to come to

this opera for the first time. As with Herheim's Parsifal, there were two

narratives working concurrently, one dystopian, the other erotic, but in

this case we were subjected to the whims of a German director determined to

sew controversy. The 69-year-old Hans Neuenfels is perhaps most famous for

incorporating roast chickens into his Aida and for using Mohammed's head in

Idomeneo, which caused a storm of protest.

We first encounter

Lohengrin during the opera's prelude, desperately trying to escape through a

locked door. Once in Brabant, he emerges less as an emissary of the grail

than an office worker, ie normal guy, who on encountering the lovely Elsa

demonstrates very human insecurities. He fidgets nervously and throws

himself at her like a lost and lonely man begging for love and approval. The

consequences of Elsa's probing questions and Lohengrin's demand for

unconditional love are recognisable human themes played out effectively in

the final act of the production. Wagner considered this to be his saddest

opera. With some sensitive acting from the two principals the erotic power

of the last act is considerable (though Patrice Chéreau might have done it

better).

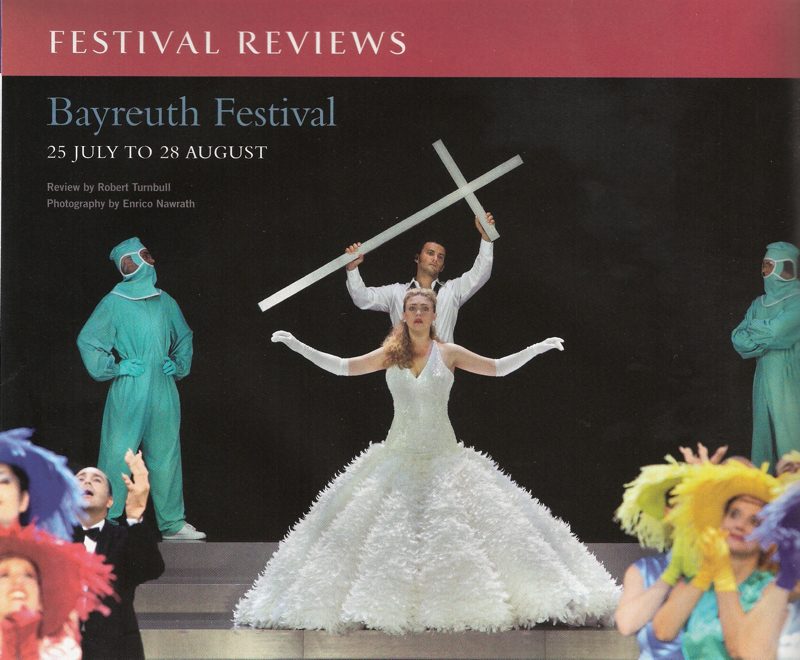

Had Neuenfels been content with telling this story, the

evening might have been less excruciating. The set is brightly lit and

clinical, a laboratory in which a ghastly experiment has turned the people

of Brabant into rats, but apparently happy, well-dressed rodents with pretty

pink tails. Yes, you've got it: the people of Brabant, like much of modern

humanity have become clones, arch consumers who will eat (or buy) anything

put in front of them and follow leaders willy nilly. These rats, moreover,

share childish humour, break dance and high five like high school kids. We

are all becoming Americans!

The symbolism continues. Elsa has arrows

stuck in her back, all of which Lohengrin removes. The swan which returns to

collect our hero from his predicament is in fact an egg, out of which

emerges a fully formed embryo which scatters its umbilical chord around the

stage like lumps of bratwurst.

Of course at Bayreuth there were

musical compensations. Opera's current sex symbol Jonas Kaufmann

used his beautiful and dark hued voice to glorious effect especially in the

final duet. In this he was matched by the burnished tones of the

Elsa of Annette Dasch. Evelyn Herlitzius (who sang Ortrud) has a boom in her

voice that suits the part, but this small-framed singer should be careful.

She is already developing a wide vibrato and her top notes are sharp. The

likeness to the British dramatic soprano Gwyneth Jones during her heyday is

remarkable. Sadly, her intensity wasn't matched by the Telramund of

HansJoachim Ketelson.

The Latvian conductor Andris Nelsons gave a

thrilling and passionate reading of the score, full of telling detail in the

woodwind and brass and shimmering strings. Like Semyon Bychkov at the Royal

Opera last year Nelsons managed to create soft cushions of sound, allowing

the principals maximum flexibility in phrasing and dynamics. It's just a

pity that his first attempt at this opera should have come with this

production.

|