|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Opera uk, November 2009 |

| Hugh Canning |

|

|

MUNICH — Lohengrin

|

|

Which

came first: the MUNICH FESTIVAL’S overriding theme, Under Construction’, or

Richard Jones’s ‘Building (and Desecration) of the House’ concept for

Lohengrin? In any case, a large proportion of Munich festival-goers seemed

unimpressed by what they saw at the second night (July 8) of Jones’s new

production, his first Wagner staging in Germany. On the first night, he and

his designer, Ultz, had been, as they say “ausgebuht” (booed off the stage).

At my performance they were condemned in absentia after each act, although

some of the protests may have been for Kent Nagano’s slick but often

superficial conducting—the orchestra and chorus didn’t sound overfamiliar

with Wagner’s score, which took me by surprise until I was informed that

Lohengrin hadn’t been in the repertoire of the Nationaltheater for most of

Peter Jonas’s tenure as Intendant: this was Munich’s first new Lohengrin in

more than 20 years. Which

came first: the MUNICH FESTIVAL’S overriding theme, Under Construction’, or

Richard Jones’s ‘Building (and Desecration) of the House’ concept for

Lohengrin? In any case, a large proportion of Munich festival-goers seemed

unimpressed by what they saw at the second night (July 8) of Jones’s new

production, his first Wagner staging in Germany. On the first night, he and

his designer, Ultz, had been, as they say “ausgebuht” (booed off the stage).

At my performance they were condemned in absentia after each act, although

some of the protests may have been for Kent Nagano’s slick but often

superficial conducting—the orchestra and chorus didn’t sound overfamiliar

with Wagner’s score, which took me by surprise until I was informed that

Lohengrin hadn’t been in the repertoire of the Nationaltheater for most of

Peter Jonas’s tenure as Intendant: this was Munich’s first new Lohengrin in

more than 20 years.

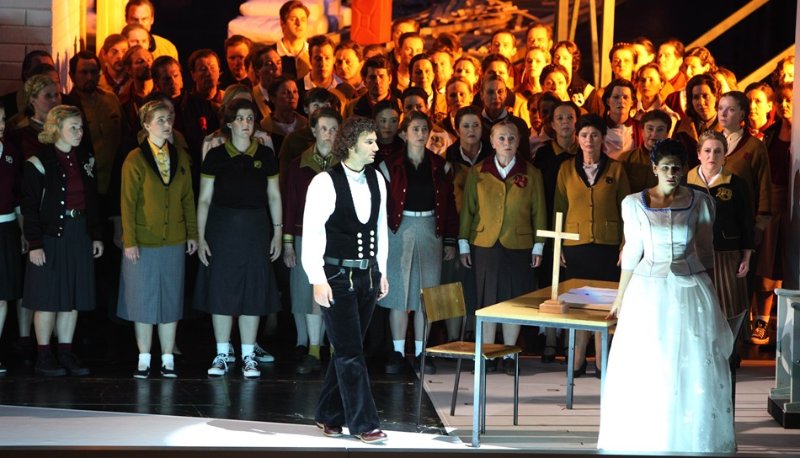

It certainly looked new, unlike any other I have seen or even imagined.

During the prelude a young woman in dungarees is drawing plans for her ideal

home on an architect’s easel, and for the remainder of the opera Elsa’s

house is built on stage— in itself a brilliant piece of stagecraft. Although

Ultz’s costume and set designs are 1950s-ish, Jones draws at least some of

his inspiration from Wagner’s autobiography. To a great extent, all of

Wagner’s heroes are projections of his own ego. He completed Lohengrin

during his exile from Germany and at a time when his relations with his

first wife, Minna, were rapidly deteriorating. So in Jones’s vision, the

Protector of Brabant, the usually shimmering swan-knight, is an ordinary

bloke in working men’s clothes — a handsome presence in the person of Jonas

Kaufmann, making his role debut in the production—who hankers after hearth

and home. In the dreamy, idealist (architect) Elsa, he thinks he has found

his conduit to them both.

As with most of Jones’s constructs, this one takes on a life of its own, so,

as Lohengrin and Elsa prepare to move into the completed house for the

wedding celebrations of Act 3, a troupe of dancing gardeners make use of the

famous prelude to put the finishing touches to a floral slogan, ‘Wo meine

Wähnen Frieden fand, Wahnfried sei dies Haus von mir genannt’, the

inscription on the first home owned by Wagner in Bayreuth. Very clever, if

ever so slightly flippant (by now, anyone who has seen Jones’s Wagner

productions—the Ring in London and Der fliegende Holländer in Amsterdam—will

know that he doesn’t take these works entirely seriously, that a part of his

response is to poke fun).

Watching his production, it did cross my mind that perhaps it is no longer

possible to take the scenario of Lohengrin seriously. Who believes in

miracle-workers these days? And those who do work miracles, Jones seems to

be saying, often turn out to be disastrous, destructive rather than national

saviours. After Elsa asks the fatal question, Lohengrin douses their bridal

bed (and the cradle awaiting the first addition to the family) in petrol,

and torches the house. This evidently proved too much for a Munich audience,

as did the caricatured burghers, some wearing traditional local dress and

standing in serried ranks beneath coats of arms, some bearing a B —for

Brabant, or Bavaria, perhaps. I was surprised by the virulence of the

hostility to Jones’s production, which seemed no more of a history lesson

than a lot of German Regietheater efforts; but maybe German audiences don’t

want to take lessons about their (recent) history from an Englishman. I

can’t say I blame them.

It’s a shame for Jones, who has had big successes at this house with his

long-playing Giulio Cesare and short-lived Midsummer Marriage. The staging

was brilliantly executed by the Munich technical team, which must be the

envy of the operatic world for creating big, architectural spectacle without

the slightest hint of a hitch. And Jones actually tells the story, albeit

very much on his own terms, with absolute clarity. Posters of the young Duke

of Brabant, marked Vermisst (‘Missing’), were pasted to the sides of the

proscenium and leafleted around the foyer—another clever touch. But, like

most Lohengrin directors, he was flummoxed by the swan. Lohengrin carrying

on a puppet and taking it into the wings to be transformed into Gottfried

really wasn’t much of a theatrical coup. But what do you do? Nikolaus

Lehnhoff, in his staging for Baden-Baden and La Scala, ignored the pesky

bird altogether, treating it as a symbol of Ortrud’s power and replacing it

with a throne that she wished to usurp.

Vocally, this was a Lohengrin to treasure: Kaufmann’s dark, baritonal but

Italianate-sounding tenor offered a new kind of Wagnerian experience for me,

ringing and heroic when necessary, but essentially lyrical: his soft

singing, almost a whisper, of ‘Mein lieber Schwan’ was spellbindingly

beautiful. And his text, of course, was immaculate. The same could be

said of Anja Harteros’s unusually proactive Elsa, a dark, smoulderingly

sensual beauty, even in her dungarees and plait, rather than the usual

wilting pushover. Michaela Schuster’s cynical, vampish, trenchant Ortrud had

a creepy whiff of Myra Hindley about her, something that might have been

lost on a German audience, while Wolfgang Koch’s Telramund and Christof

Fischesser’s Henry the Fowler were both outstandingly well sung. What a rare

treat to have five native speakers of such high vocal quality in Lohengrin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|