|

|

|

|

|

|

|

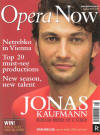

| Opera Now, September 2011 |

| Ingrid Gäfvert |

Hitting the heights

|

|

|

|

With his brooding good looks and a versatile voice that has power and personality, Jonas Kaufmann is today's tenor of choice in leading opera houses aroundd the world. Ingrid Gäfvert catches up with the singer as he plans the next steps in his extraordinary career. |

|

|

THE

DISTINGUISHED-LOOKING FIFTY SOMETHING gentleman sitting next to me is

sobbing audibly. As I look around, the discerning but usually

undemonstrative audience at the Vienna State Opera is full of people openly

weeping, captivated by what they hear. THE

DISTINGUISHED-LOOKING FIFTY SOMETHING gentleman sitting next to me is

sobbing audibly. As I look around, the discerning but usually

undemonstrative audience at the Vienna State Opera is full of people openly

weeping, captivated by what they hear.

On stage, Jonas Kaufmann is

singing Werther's romantic reverie 'Pourquoi me réveiller' with soulful

abandon. It's a performance that exudes star quality, radiant, deeply felt

and with a personality of its own.

Not that he is flawless. Kaufmann

has a superbly dark, expressive voice, but there is a grainy roughness

around the edges that's part of its character. Then again, quality singing

is never merely about technical perfection. True operatic genius lies in the

ability of a singer to breathe life into a character, so that the illusion

on stage becomes a reality for the spectators. The audience in Vienna were

there to be in the presence of Jonas Kaufmann, opera's new tenor superstar;

but by the third act they are completely 'absorbed in the sorrows of the

dreamy young poet, Werther.

This ability to get under the skin of

every character he portrays has been pivotal in the blossoming career of the

42-year-old German tenor, as has his varied choice in repertoire, which

includes Lieder, French and Italian opera as well as the German roles -

Wagner in particular - that he is increasingly shouldering.

His debut

in Wagner's Lohengrin in his home town of Munich in the summer of 2009 had

thousands flocking to the outdoor relay in front of the Bavarian State

Opera, celebrating the return of the city's prodigal son, listening with

hushed pride. All talk was of Kaufmann's unusually Italianate approach to

Wagner, singing in long phrases, beautifully nuanced and with plenty of

light and shade - a far cry from the heroic shouting match that you often

get in this role.

When I meet him, he is performing in Carmen in the

same theatre, struggling with a bad cold, but soldiering on so that you'd

hardly know it. Backstage after the show, the stage-door is besieged by

excitable fans. But it's not the brooding Byronic hero of the record covers

and posters who arrives to pose for endless photos and sign autographs; it's

a relaxed, polite fellow who goes out of his way to make sure that everybody

gets their moment of his undivided attention.

The next morning in the

breakfast-room of his hotel, Jonas Kaufmann is engaged in germ warfare,

battling coughs and sniffles with a bright green vitamin concoction, which

he downs along with gallons of sugary coffee. Even in this condition, he can

turn on the charm. He is unstintingly energetic and talkative, though

clearly a bit weary of the `tenor hunk' tag. He puts up with my own effusive

admiration (okay, I just can't help myself) gracefully.

Work, he

admits, nowadays engulfs his life more or less completely, but I get the

distinct sense he's enjoying it all immensely. `I have the luxury of

choice,' he says, with evident relief that in his pursuit of a difficult,

demanding career, he's come out on top. `I'm able to schedule the things I

feel are right for me, in the right combinations and in the right order. I

can really think about where I want to go vocally and what I need to get

there. I'm building a solid foundation to reach those targets. Every time I

take a step into a heavier part of the repertoire, I try to balance it with

less heavy roles, and hopefully that will keep the voice healthy and lasting

a long time.

Kaufmann is serious about his work, but that's because

he really relishes what he does: `How good you are on stage depends not just

on your experience and vocal skills, but also on how much you really want to

be there. Of course the level of my hunger for performing varies, but I

always try to find the right appetite and incentives. You have to challenge

yourself to keep finding new aspects of the characters you sing, to keep it

all interesting and alive.'

Since he's in a position to pick and

chose where he works, Kaufmann likes to get involved in the early stages of

the planning process of the productions he sings in. `I think it is also

nice for the opera houses where I work to know that I'm dedicated to these

projects as one of the team. They are my "babies", and it gives it all an

extra energy. To be able to bring influence to my work is the best possible

safeguard against losing my sense of joy in doing this job.

`It can

happen you know. I always think to myself, "Who knows what I will be doing

in six or seven years? maybe I'll open a pub!" It's sort of joking of

course, but there is also a glimmer of truth. Once you've done it all, where

do you go?' Kaufmann has extraordinary reserves of lightly worn

self-confidence. He's a man with a plan that he likes to stick to. But

there's a wobble of uncertainty here. Where indeed would he go if his voice

failed him? (Perhaps at the back of his mind is his contemporary Rolando

Villazon; another dark, handsome, brooding tenor whose burgeoning operatic

career went off the rails when he discovered he needed major surgery on his

vocal cords.)

Pausing for thought, Kaufmann devises `Plan B': if

something happened that made him unable to continue singing, he wouldn't

keep `a foot in the door' of the opera world. `I'd probably do something

completely different. My grandparents had a farm and there was always

something to do, something to fix or build, and I love that. I carry a

tool-box around every chance that I get. When I did Werther in Vienna last

month, I had a very nice apartment, but there were some minor things that

needed fixing, so I got right onto it.'

For now, however, the role of

handyman remains a hobby (though it must have come in useful when he had to

physically build a house on stage as part of Richard Jones's controversial

production of Lohengrin).

When he does put his tool-kit aside, you'll

find him practising his art: he sings every day, sometimes, he says, even

without noticing he's doing it. `I don't sit at the piano singing scales,

but singing is always there somehow. And while I'm learning a new role,

little snippets of it always keep popping up - usually things that I need to

work on some more, so it's a good indicator as to what progress I'm making.'

Vying with opera for his affections is Kaufmann's love of Lieder. He's a

rare breed of tenor that can make the transition from full-blooded heroic

Wagner roles to the gentle nuances of Schubert song - Covent Garden one day,

Wigmore Hall the next. `I could happily take a year off from opera and do

only Lieder,' he says. `That would be a dream! There is so much left to

discover in the song repertoire, and it is really healthy for the voice. I

try to keep some time set apart for song recitals every year and will keep

doing that. You can do so much with Lieder, but you also have to be very

well prepared. There is no costume, no orchestra to hide behind, it is all

about you.'

International travel is a constant for any successful

opera singer today, and most of us might suppose that the glamorous part of

the job is to get to see new and interesting places. But the globetrotting

singer says that time for exploring is usually scarce - the most he gets to

see is the inside of a darkened theatre.

He does pop into museums

when he can though - he's taken out membership of several around the world.

°I love to go to the Louvre if I have an hour on my hands, perhaps to see

just a few objects, but to really see and enjoy them. It is wonderful to

explore paintings and to let the imagination roam. And it's extra special to

get the chance to visit museums with my children. They have such open minds

and vivid imaginations, something that we adults should hang on to much

more.'

With the nomadic life he leads, the tenor says it is hard to

keep in touch with old friends outside the business. `Thankfully they accept

that I am not often around and that it can be a long time between seeing

each other, when I am completely focused on work and giving it my all. With

my friends I can be very spontaneous. When I get home, I go shopping for

groceries and start cooking, which I really enjoy. Suddenly my wife peers

into the pot and says, "Jonas, this is for 15 people, not five!" So we call

some friends and in half an hour they are there, and that's great.

His wife, Margarete Joswig, is also a singer (a Wagnerian mezzo), though

she's put a budding career on hold while the children are growing up.

Domestic life for Kaufmann seems unusually blissful in a profession that

often puts massive strains on the family. The children, a daughter aged 12

and two sons, seven and five, are all used to opera and enjoy it, though

their parents try not to take them too often. `I want my kids to think of

opera as something special and to be enjoyed, not as the thing that is

always taking me away from them,' says Kaufmann. `When I do a new opera,

even if they don't get to see it, my wife and I play bits of the music and

explain the story to them. When it came to Walküre, I was not sure if it was

the right story to tell - what with all the incest and dysfunctional family

feuds. But it turned out very well! My elder son loves the Ring and now we

hear the music coming from his room all the time. He actually came to me and

said, `Why do you have to sing Siegmund, daddy? Why can't you sing Siegfried

- he's so much better!"

Many opera lovers would wholeheartedly

endorse Kaufmann junior's view of his father's future career choices. The

prospect of Kaufmann as Siegfried is thrilling. And for the DIY supremo who

lurks within our tenor superstar, the role will be another strong bolt in a

carefully crafted career.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|