|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Opera News, December 2012 |

| DAVID J. BAKER |

|

|

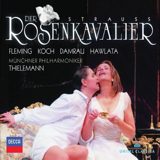

R. STRAUSS: Der Rosenkavalier (CD)

|

|

It's

easy to forget that this finely coordinated Rosenkavalier was recorded at a

live performance. Whether as a result of German etiquette or German

engineering, the audience at Baden-Baden on this occasion in January 2009 is

mute. The floorboards make not a whimper; voices and instruments emerge with

warmth and clarity. And the moments of quiet lyricism that most distinguish

the performance, especially in the Marschallin's pivotal scenes late in Act

I, achieve a rare degree of intimacy and directness. It's

easy to forget that this finely coordinated Rosenkavalier was recorded at a

live performance. Whether as a result of German etiquette or German

engineering, the audience at Baden-Baden on this occasion in January 2009 is

mute. The floorboards make not a whimper; voices and instruments emerge with

warmth and clarity. And the moments of quiet lyricism that most distinguish

the performance, especially in the Marschallin's pivotal scenes late in Act

I, achieve a rare degree of intimacy and directness.

Christian

Thielemann, a supportive conductor with singers (nowhere more so than in the

tenor monologue in his Vienna Tristan a few years ago), helps to make this a

great occasion for Renée Fleming in one of her best roles. The conductor

ideally cushions her slow, poised unfolding of the Marschallin's

introspective lines, keeping the instrumental texture feather-light. The

effect is like witnessing an inspired accompanist in a seasoned lieder

partnership.

Fleming has always relished details, and in this case

they feel natural, motivated, part of the fabric. The monologue's final

line, about bearing our inevitable fate as mortals — "und in dem 'Wie' da

liegt der ganze Unterschied" (and the how is what makes all the difference)

— becomes a resonant thumbnail portrait of the Marschallin; we hear both the

pain and the forbearance, her depth and her charm. The word "wie" glows

warmly and is echoed in the inflection of the same vowel in "Unterschied";

but the lightness of the phrasing is what really counts.

At soft

volume, Fleming skillfully brightens her rough lower register to maintain

the wistful mood. Elsewhere, too, the quieter moments have true Straussian

elegance — in her G on the word "Rose" and especially her radiance

throughout most of the final trio. Full-voice attacks can be a little raw,

but in the expressions of anger at Ochs in Act III they have dramatic

relevance. Early in the opera, both Fleming and the Baron Ochs, Franz

Hawlata, lack the ideal power for the fast, hectic dialogue, but they

compensate with rhythmic agility, vocal characterization and — not only in

his case — comic details such as Viennese dialect.

Diana Damrau's

dynamic Sophie is memorable for her glistening high notes and graceful

phrasing, an ideal rendition of youthfulness and rapture. She risks

harshness in voicing the young woman's arriviste pretensions early in Act

II, but her disappointment just before the happy end is also vividly

portrayed, helping to maintain dramatic tension. Sophie Koch's mezzo is not

quite robust enough for the role of Octavian, in which the singer must

provide dark counterpart to the sopranos and sometimes compete in the

soprano range. But this artistic singer clearly grasps the character's

exuberance and warmth.

Whether he is deliberately pampering a

light-voiced cast or sees this as a fundamentally pastel, nostalgic work,

Thielemann's tempo choices produce one of the slowest, longest versions of

Der Rosenkavalier on disc, even among live recordings. While it makes all

the traditional cuts in Ochs's scenes, this performance still runs longer

than the uncut versions by Erich Kleiber and Georg Solti. The result is not

leaden, although it is surprising in a conductor known for dynamism.

The approach suits the Marschallin's scenes as well as the Italian

Tenor solo, a fine, deliberately paced legato performance by rich-toned

Jonas Kaufmann, who is almost too smooth to mark the sixteenth-note runs as

more than a portamento. Other slow-motion scenes are less effective.

One occurs in the opening dialogue between the lovers, which at

least gives Koch's Octavian a chance for some expansive phrases; more

serious is the halting "presentation of the rose" scene, which loses some of

its magic at the eyedropper pace. Some comic touches, such as the Annina and

Valzacchi ensembles, would gain from acceleration, as proven in Carlos

Kleiber's live video versions.

One detail confirms the lyrical bias.

There is almost a transformation of the oafish Baron Ochs in his final

realization ("Mit dieser Stund' vorbei" — from this moment, it's all over),

where the pace comes to a crawl and Hawlata's Baron accepts his losses, not

as the score suggests in outrage, but in an uncharacteristic phrase of

refined mezza voce in a tenorial head tone.

Ochs's boisterous exit

music restores excitement, with infectious rhythms and some especially fine

flourishes from the Munich Philharmonic horns; generally, Act III is

livelier than the others. But that gossamer "Mit dieser Stund' vorbei"

lingers in the memory. It wins sympathy for the comic villain, yes, but it

also makes him sound not just foiled but emasculated — perhaps even

enlightened. Here, Baron Ochs has, in effect, his own Marschallin moment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|