|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Opera News |

| MATTHEW GUREWITSCH |

|

|

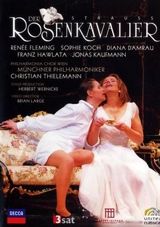

Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier

|

|

Herbert

Wernicke's Rosenkavalier originated in 1995 at the Salzburg Festival and was

seen subsequently at the Paris Opera. Recorded on January 31, 2009, the

revival at the Festspielhaus in Baden-Baden certainly has its moments. The

presentation of the rose, conventionally played as the most public of

ceremonies, is staged this time as private fantasy. Palace walls split open

to reveal a black staircase to paradise straight from vaudeville. A Pierrot

in blackface sits on an upper step holding the case for the silver rose, but

the star is Octavian, who stands in white tie and tails — a dead ringer for

Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus, right down to the diamante lapels. It's

sheer magic, in complete accord with the ice-crystal filigree of the music. Herbert

Wernicke's Rosenkavalier originated in 1995 at the Salzburg Festival and was

seen subsequently at the Paris Opera. Recorded on January 31, 2009, the

revival at the Festspielhaus in Baden-Baden certainly has its moments. The

presentation of the rose, conventionally played as the most public of

ceremonies, is staged this time as private fantasy. Palace walls split open

to reveal a black staircase to paradise straight from vaudeville. A Pierrot

in blackface sits on an upper step holding the case for the silver rose, but

the star is Octavian, who stands in white tie and tails — a dead ringer for

Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus, right down to the diamante lapels. It's

sheer magic, in complete accord with the ice-crystal filigree of the music.

Throughout the twentieth century, Der Rosenkavalier seemed the opera more

fixed in amber than any other. But times change. At the dawn of the

twenty-first, Peter Konwitschny set Act I of his controversial Hamburg

production in 1740 and Act II in the 1920s, splitting Act III between the

present and a department-store window in the year 2050. Octavian dressed as

a woman when Strauss and Hofmannsthal meant him to appear as a man, and the

other way around.

By that standard, departures from tradition that may have seemed

revolutionary when Wernicke's production was new look inconsequential now.

The action is updated to the 1930s, which means no powdered wigs, except for

lackeys in uniform. At curtain rise, Octavian is sitting on a chair in boxer

shorts, knees wide, smoking a post-coital cigarette. Valzacchi reads La

Repubblica. Ochs struts in a loden jacket and lederhosen. His relationship

with his strapping bastard son Leopold (a mute part) is intense. Between the

two stanzas of his song, the Italian Singer — a Uomo Vogue fashion plate,

his cheeks sculpted by a five-o'clock shadow — takes hard knocks from foot

traffic but finds consolation in a plate of spaghetti. Late in the evening,

contradicting the libretto, the Marschallin and Faninal ride off in separate

coaches. Rather than take their final exit, Octavian and Sophie recline side

by side at center stage, where Pierrot tosses Sophie's silver rose aside,

replacing it with a real red one. Down with artifice! Now real life begins,

in all its fleeting beauty.

The set is one of Wernicke's beloved boxes of mirrors, which turn to reveal

flat renderings of palatial interiors, or, in the finale, a gloomy park.

(Unaccountably, the Marschallin's boudoir and the Act III country inn are

identical.) The predominantly red-and-white color scheme is sumptuous, the

furnishings and costumes are deluxe. But the performance feels more

assembled than alive.

Distracted, glamorous in every way, bristling with impatience behind an

impassive façade, Renée Fleming's Marschallin inhabits a world of her own.

Sophie Koch's velvet-voiced Octavian is most haunting in silence, seen from

behind, swinging a rapier like the pendulum of one of the Marschallin's

clocks. Elsewhere, Koch mugs like a manic Chaplin. Only Diana Damrau, who

catches Sophie's raptures with the same immediacy that marks her tantrums,

insecurities and disappointments, draws her costars into moments of real

intimacy.

Franz Hawlata has as strong a claim to the boorish Ochs as anyone today, but

this time out, the microphones capture his voice in gnarled and frayed

condition. Looking like the proverbial million bucks, tenor Jonas

Kaufmann's Italian Singer gets star billing, and he deserves it, both for

his ardent vocalism and for his witty execution of his slapstick business.

In the pit, Christian Thielemann shows a command of the score's myriad

subtleties that is arguably as encyclopedic as that of the legendary Carlos

Kleiber, and he takes expert care of the cast. Yet the moments that ignite

most memorably are boisterous, purely instrumental episodes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|