|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bay Area Reporter, San Francisco |

| by Tim Pfaff |

|

|

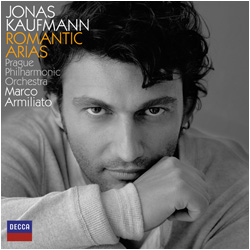

Romantic Arias

|

|

|

There are few faster ways to end a musical career prematurely than to be

opera's Next Thing. And, on evidence, if looks could kill, they'd conspire

in the demise, too. At a time when the bodies are piling up in the wings,

a likely survivor of the grisly process is Jonas Kaufmann, the 39-year-old

German tenor who recently weighed in with his first opera CD, Romantic

Arias (Decca). There are few faster ways to end a musical career prematurely than to be

opera's Next Thing. And, on evidence, if looks could kill, they'd conspire

in the demise, too. At a time when the bodies are piling up in the wings,

a likely survivor of the grisly process is Jonas Kaufmann, the 39-year-old

German tenor who recently weighed in with his first opera CD, Romantic

Arias (Decca).

Even more than his ringing voice and gripping stage presence, it's

Kaufmann's range as an artist that has secured him a place in the

present-day opera pantheon. Even when he was the new kid on the block, he

performed like one with uncommon instincts. It's turned out far more often

than not that if he thought a role was for him, it was, vocally and

dispositionally. Simply put, when he's onstage, you don't think about the

great singers from the past in the same roles.

Varied as they are, the 13 selections on the new disc only hint at his

range, leaving out the Monteverdi at one expressive extreme and the

Beethoven Florestan at the other. Surprisingly well-accompanied throughout

by the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra under Marco Armiliato, they show a

singer in his vocal prime with a secure technique who is, above all, a

creature of the stage. The great items aren't the ones on which he is

speculating, artistically; they're the ones he's scored his triumphs with

in the house.

The singing has impact. Don Jose's "Flower Song" from Bizet's Carmen

doesn't always reveal the whole character, but the full, tragic dimensions

of the soldier, doomed from the start by an obsessive love, are present in

Kaufmann's performance, alongside uncommon refinement. The sweep of his "E

lucevan le stelle," from Puccini's Tosca, brings the full weight of

Cavaradossi's struggle to an aria that can all too often become a static

showpiece.

The three Verdi selections, the Duke from Rigoletto, Alfredo from La

Traviata, and Carlo from Don Carlo, all show the deep involvement his

stage portrayals have given them. Still, it's Carlo's "Io la vidi" that

sounds as if it has been snatched from a live performance. The voice is

plangent, the phrasing masterful, but it's the urgency of this soul in

distress that grabs you by the throat.

The French selections are some of the best on the disc. Berlioz's ecstatic

Faust is given full voice, but Gounod's more lovesick one is no less

involving. Massenet may be a newcomer in his repertoire, but there's

already great sophistication in his Des Grieux, and the ache in his

"Pourquoi me reveillier," from Werther, brings the disc to a stirring

close.

The industry gurus let some things slip. The killer tessitura of "Ach, so

fromm" leaves the tenor hanging by his eyebrows, as it has so many others,

and the aria could have been dropped or replaced. And who let the audible

croak at the start of the middle stanza of Walther's Prize Song from Die

Meistersinger get by the audio editors? But this time the devil is not in

the details. The thrill, and there is a palpable one, is in hearing a

voice of this quality let rip.

There isn't another tenor working today I'd rather hear sing whatever he

chooses. His rise to the ranks of the truly great depends only on only one

thing, over which he has no control: whether the sound of his voice

lingers after the disc stops spinning or the curtain drops. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|