|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gramophone |

| John Steane |

|

|

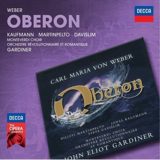

Weber: Oberon

|

| Hillevi Martinpelto sop Reiza ;

Frances Bourne mez Puck ; Marina Comparato mez Fatima ;

Katharine Fuge mez Mermaid ; Steve Davislim ten Oberon ; Jonas

Kaufmann ten Huon ; William Dazeley bar Sherasmin Monteverdi

Choir; Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique/John Eliot Gardiner

Philips New CD 475 6563PH2 (123 minutes) Reviewed: Awards 2005 |

|

| A fine set that overcomes the many problems

posed by this magical opera |

|

In

the opera, Sir Huon has only to blow his magic horn (if he can find it) and

Oberon will come to the rescue. On stage, the opera itself stands much in

need of a similarly magical way out of its many problems. The fairy world of

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is crossed with medieval chivalry, romantic

aspiration and a setting of Arabian Nights. The scene is forever changing,

and the musical idiom shifts from the purest moonshine (foretelling

Mendelssohn) to the kind of cosmic grandeur that later spelt Wagner. In the

original version, spoken dialogue keeps up the dramatic pretence, but that’s

all it is, for the characters and situations have little chance of gaining

even the credibility of suspended disbelief. In

the opera, Sir Huon has only to blow his magic horn (if he can find it) and

Oberon will come to the rescue. On stage, the opera itself stands much in

need of a similarly magical way out of its many problems. The fairy world of

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is crossed with medieval chivalry, romantic

aspiration and a setting of Arabian Nights. The scene is forever changing,

and the musical idiom shifts from the purest moonshine (foretelling

Mendelssohn) to the kind of cosmic grandeur that later spelt Wagner. In the

original version, spoken dialogue keeps up the dramatic pretence, but that’s

all it is, for the characters and situations have little chance of gaining

even the credibility of suspended disbelief.

In this version, as at last year’s Edinburgh Festival, the spoken dialogue

is removed and a narrator’s voice substituted. It works well (better than at

Edinburgh) because the speaker can use a quiet, intimate, story-teller’s

voice, and we probably find it easier to accept this as a convention than to

acquiesce in an attempt to make theatrical realism out of it. In this form,

too, we listen without distraction to the music, and find ample delight in

that.

The famous overture isn’t typical, still less ‘Ocean, thou mighty monster’,

the soprano’s equally famous aria. The distinctive idiom of Oberon lies more

in its choruses of elves and elemental spirits, and in numbers like the

Quartet in Act 2 and the charming duet for Fatima and Sherasmin. Depth of

feeling is there in Huon’s prayer and Rezia’s cavatina (the heroic element

of the ‘big’ solos somehow less germane). But altogether a good performance

– such as this is – leaves little doubt that the work deserves its revival:

and it would be, surely, a very resolute purist who could entirely banish

the stark biographical facts. The premiere took place at Covent Garden on

April 12, 1826, and by May 30 Weber was lying dead at Great Portland Street.

The immediate rival (the strongly cast 1971 Kubelík set – DG, 12/91 – is no

longer listed) is under Marek Janowski. Gardiner is more poetic, the fairies

lighter on their feet, the quieter passages more private. Recorded at a

lower level, it makes more of contrast between relaxations (in the Mermaids’

song, for instance) and tensions (good at the gathering storm). The soloists

are less forwardly placed but characterise vividly in compensation.

Best is Jonas Kaufman’s Huon. The tenor is supposed to possess the heft

of a Tannhäuser while performing graceful flourishes in the manner of

Rossini’s Count Almaviva. Kaufman brings all the lyrical sweetness and

technical skill for that part of it, and can still produce extra power and

ring for the heroics. The heroine is sung with less distinction by

Hillevi Martinpelto. Ideally the part calls for a voice of melting beauty (a

Tiana Lemnitz perhaps) for the ‘vision’ solo and the cavatina, and the

strength and nobility of a Brünnhilde in the ‘Ocean’ aria: this Rezia falls

rather ineffectually between.

The others do well, the Fatima taking full advantage of her two attractive

solos and the Oberon keeping his voice light and distinct from Huon. The

Monteverdi Choir make a point of singing in character and with attention to

the dramatic situation. Perhaps the decisive factor for many will be

language: this performance is sung in English, which for once can be claimed

to be authentic. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|