At the if-you're-somebody-you-have-to-be-there level, the big-ticket

item in opera this summer was the Bayreuth Festival's new production of

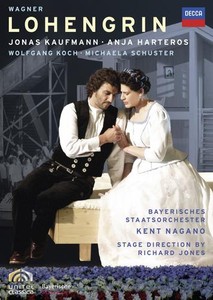

Wagner's Lohengrin, with the more-handsome-by-the-day Jonas Kaufmann in

the title role. To gander at the stills, the comely Kaufmann looks a

trifle bored among the lab rats with which the animal-fetishistic

director Hans Neuenfels littered the Festspeilhaus stage. I suppose

that's one way to take attention away from that pesky swan Wagner left

directors to deal with, but maybe, as everyone said, you had to be

there.

Those of us who could not bip off to Bavaria in our

private jets got a juicy consolation prize by way of Decca's nearly

simultaneous release of a DVD of Kaufmann's debut in the role in the

Bavarian State Opera's new Lohengrin last summer. Its director, Richard

Jones, knew better than to try to get between Kaufmann's virility and

the people who love it, but, that said, he did put the tenor and the

entire cast in a thought-provoking production that at least didn't

trivialize the work. Perhaps oddest of all, it just let the swan be

there, plunk, as a no-doubt-about-it swan right where Wagner specified.

Jones places the story in a society in what feels like

between-the-world-wars Germany, a state in a proto-totalitarian stage of

seeking a new leader. His production – realized on the stage by the

cryptically named designer Ultz – works well at the level of telling a

story his Munich audience might relate to. It has all the consistency

Wagner's highly problematic libretto allows.

Ultz's signature

stage pictures feature mostly flat planes in strong, saturated though

not quite primary colors. There's a nod toward the traditional Lohengrin

soft blue, but here the centerpiece is the white brick house Elsa is

building, brick by brick, in her coveralls, as she awaits with

supernaturally focused patience the arrival of the man of her dreams –

who, when he does arrive, helps with the bricklaying.

Jones'

concept made the role of the Herald – here the propagandist public voice

of an Orwellian authority, keeping a cowed public "informed" from behind

a big, cobalt microphone – make sense to me for the first time. Where

the sharp-lined pictures go blurry for me is in the way the production

depicts the contenders for leader of this anxious herd all too eager to

be governed.

Ortrud and Telramund, usually presented with almost

cartoonish, Boris and Natasha unalloyed, oozing malevolence, are a

comparatively bland couple here, and any sense of Ortrud's being from

the dark side is sacrificed to her almost glow-in-the-dark blond wig,

which all but screams Aryan. Who are these people? It's hard to take

them seriously, and it doesn't help that the singers, Wolfgang Koch and

Michaela Schuster, lack zoots and are little more than obedient to the

notes and the stage direction.

Wagner's quandaries are greater

than Jones and Ultz could either solve or complicate, but at

least Jones keeps us on the line while the ravishing performances by

Kaufmann and Anja Harteros, as Elsa, play out. They are the dark,

smoldering beauties of this production, though you wouldn't for an

instant miss that they're German. But the purity they exude is not the

Aryan variety, and singing as sensitive yet intense as these two offer

comes along once in a decade, if that. Kaufmann's "In fernem Land" is

pure transport, sung as if on a single breath, hushed and heroic in one

long, smoldering arc.

|