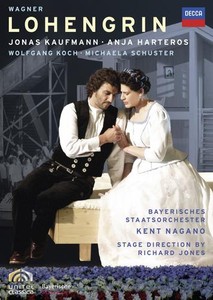

Every new production, no matter how willful, seems to have its champion

in the press, but not Richard Jones's Lohengrin, the debacle of

last year's summer festival at the Bavarian State Opera. The ranking

German critics tarred and feathered it; my impression at a mid-run

performance was that they had been kind. But the cast was

praised to the skies, especially Munich native Jonas Kaufmann in his

role debut as the hero — which also marked his homecoming to a house

that had never thrown him a crumb early on. To my mind, Kaufmann

exceeded the brightest expectations, eclipsing his colleagues

completely.

The video does him justice while at the same

time working wonders for everyone else. Blessed with the leonine face

and mane of Leonardo's Vitruvian Man, Kaufmann conveys an ecstatic

otherworldliness. Swirling through the Act I duel, heedless of

Telramund's fumbling, he embodies an exterminating angel. Throughout,

his bearing, gestures and expressions reflect the isolation of a proud

and righteous soul. Incredibly, he delivers the great narrative of the

Grail sitting in a chair, which would seem to put him at a disadvantage

but somehow doesn't at all. Bleak yet radiant, working the material in

the subtlest shadings of timbre, mood and attack, Kaufmann puts before

us Lohengrin's inner landscape of love, loss and awe.

With the chalk-white face, ink-black curls, wide

crimson smile and level gaze of a Minoan princess, Anja Harteros is

ravishing in close-up as Elsa, and she shapes her music with clarion

passion. Wolfgang Koch, the rumpled Telramund, gives a bruising account

of his character's pain and outrage. In her blonde bob, Michaela

Schuster's Ortrud looks like a heavy-set Edie Falco, and the play of her

features, whether she is singing or silently scheming, gives a viewer

plenty to watch. In the house, she sounded like an overextended

chanteuse, but onscreen her vivid diction and clear projection carry the

day. In Christof Fischesser, the production has a sonorous,

anxiety-ridden King of tremulous integrity. His mobile eyebrows speak

volumes. (The same is true of Kaufmann and Harteros, though they send

very different messages.) Perched on an umpire's chair, with Groucho

specs and an off-kilter wedge of marcelled hair, Evgeny Nikitin sounds

the Herald's bulletins with authority. Kent Nagano, whose conducting

felt square and nondescript in the house, comes off here as efficient

and occasionally eloquent.

Ah yes, the production. Jones and Ultz, his designer,

are both British, but their image bank is Walmart-meets-Oktoberfest.

Lohengrin arrives in a T-shirt and running shoes but dresses for his

wedding like peasant royalty in his Sunday best. Pinned-up braids

abound, as do coats of arms, selectively emblazoned in Gothic lettering.

The newlyweds move into a new two-story home of Elsa's design, the

interior all knotty pine. (It rotates, too.) Through much of Act I, Elsa

(in overalls) is seen laying brick for the place, a task in which

Lohengrin, an army of extras, and momentarily even Ortrud assist. A

flower bed at the footlights spells out the dedicatory couplet Wagner

wrote for Wahnfried, his Bayreuth home, where, as he said, his delusions

came to rest. Betrayed by Elsa, Lohengrin torches the wooden cradle for

the child the couple will never have.

Thus, Jones and Ultz let their cat out of the bag.

What, they ask, is Lohengrin but Wagner's sublimated fantasy of

house and hearth, projected onto Elsa, and through her, onto the hero?

In the theater, the juggernaut production that was mounted to realize

this reductive thesis crushed the performers in the dust. On video,

their searing emotional veracity blasts the show to very occasionally

distracting smithereens.

|