|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Classics Today, June 5, 2010 |

|

Robert Levine |

|

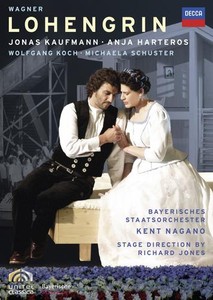

Lohengrin |

|

|

Director

Richard Jones has brought a one-dimensional concept to Munich's new

Lohengrin, recorded in July, 2009. Just as his dark, joyless Hänsel und

Gretel at the Met was "about" hunger and so he replaced the forest in

Act 2 with a dark dining room and gave us a scene-changing scrim

depicting what seemed like a gaping, bloody mouth after a visit to a

sadistic dentist, here his focus is on hearth and home--domestic bliss.

In fact, that is one of the opera's points--that Lohengrin and Elsa will

live happily ever after if only she does not ask you-know-what. Director

Richard Jones has brought a one-dimensional concept to Munich's new

Lohengrin, recorded in July, 2009. Just as his dark, joyless Hänsel und

Gretel at the Met was "about" hunger and so he replaced the forest in

Act 2 with a dark dining room and gave us a scene-changing scrim

depicting what seemed like a gaping, bloody mouth after a visit to a

sadistic dentist, here his focus is on hearth and home--domestic bliss.

In fact, that is one of the opera's points--that Lohengrin and Elsa will

live happily ever after if only she does not ask you-know-what.

Well, there is no domestic happiness without a nice house, and so from

the moment the curtain rises, Elsa, in work overalls with hair simply

braided, is drawing a picture of a house, and for the remainder of the

next two acts everyone helps with the building. (The set is by

Ultz--just "Ultz".) The home is a microcosm for the country, and in this

case the country is in disarray since the Hungarians have invaded

Germany. Start from the ground up and everything else will follow. I am

giving Jones the benefit of the doubt, by the way--maybe it's just about

building a happy life and a house, and the bad guys are incidental. Sort

of like the theme of fear or the Witch in Hänsel und Gretel.

Posters with the picture of a young boy (Gottfried, the heir) with the

word "Vermisst" (missing) are on the walls. Lohengrin's entrance is

straightforward and lacks pomp and/or circumstance, and except for the

fact that he is carrying a swan (shouldn't it be the other way around?)

he's just a regular Joe. He needs a shave and looks as if he just came

from a pick-up basketball game, wearing a blue tee shirt (untucked) and

track pants. He duels "magically" without touching Telramund.

Dress is military for some (very brownshirt-ish), and school sweaters

with insignia or sports jackets for others. The Herald, in a brown tweed

suit, sits on a lifeguard's chair and makes his pronouncements into a

microphone (not amplified, just a prop). For his wedding, Lohengrin

changes into typical Bavarian gear, including, yes, a funny hat and

lederhosen; Elsa has let her hair down and given up her overalls in

favor of a simple white bridal dress. Eventually the whole chorus is

wearing blue, untucked tee shirts. Ortrud, save for her platinum blond,

Aryan, page-boy wig, is otherwise quite ordinary and Telramund is a

nasty, sloppy bully. The house is finally built--kitchen table, bed,

baby cradle and all, with a lovely planted garden, but at the close of

the Bridal Chamber Scene, Lohengrin, left alone after the great

betrayal, sets it on fire, cradle first.

The closing curtain presents a tableau of the entire cast on

barracks-like cots, pointing guns to their heads. Mass suicide? Was

Lohengrin just a cult leader, who, upon departing, leaves everyone to

die? And, by the way, he signs his name at the wedding ceremony, so

what's the big revelation in the Bridal Chamber Scene? In other words,

Jones' concept can and does make some sense at moments, but then it just

loses steam; it's half-baked. He has taken one of the echt-Romantic

operas and turned it into something entirely different. No scary forest

in Hänsel und Gretel for him.

Musically, we have an entirely different story. Not only does Jonas

Kaufmann look great--albeit like your neighbor rather than a Knight of

the Grail--he acts well and he shades his phrases so handsomely that

everything matters; he is a caring, attentive, guy whose grief at being

betrayed overwhelms him. The voice is not a true Heldentenor; rather it

is a grand lyric. For "In fernem land" he looks straight ahead; singing

slowly and quietly, as in a trance, he tells his story. The first lines

are whispered, and the sudden rise to forte at the word "Grail" is big,

blossoming, and as radiant as the object itself. Throughout, his use of

dynamics, his ability to take long phrases in one breath, his

concentration--particularly under these circumstances, where his music

is extraordinary and his behavior is meant to be like everyone

else's--are masterful.

Almost matching him in sheer loveliness is soprano Anja Harteros. Made

to look as ordinary as an Amish farm girl, she sings radiantly. She is

not treated like a princess and therefore resentment for her by Ortrud

and Telramund just seems like spite. But never mind: her "Euch luften"

is magnificent; her growing mania after the wedding is palpable; the

sadness that pervades her being as Lohengrin sings his final narrative

(a close-up reveals a tear in her eye) is truly touching.

Both Ortrud and Telramund are under-characterized in this production.

She, in the person of Michaela Schuster, sings with absolute ease but

too placidly, and he, with a fine snarl to his big voice, is merely a

bully who is abusive to Elsa in Act 1. Evgeny Nitikin, up on his tall

chair, announces with authority as the Herald, and Christof Fischesser

as King Heinrich, who might just be the local mayor, sings impressively.

Of course none of the musical success would be possible without Kent

Nagano's leadership. Just as his Opus Arte DVD performance from Baden

Baden (in Nichloas Lehnhoff's production) is perfectly judged, so is

this one: "In fernem land" is slower and even more focused here, but

otherwise we have a very similar approach, despite the differences in

productions. And the Munich forces play stunningly for him. But picture

this: The Prelude in Baden Baden is accompanied by a white light from

the rear of the stage from which Elsa emerges like a vision; in Munich

it accompanies a nice girl in pig-tails drawing a picture of a house.

In short, Kaufmann and Harteros are remarkable, but so are Klaus Florian

Vogt and Solveig Kringelborn in Baden Baden, and that production, though

daring in concept (Wagner himself is the star), is more of a piece. This

one is humdrum to look at and works too hard to prove its single point.

Both picture and sound are brilliant. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|