|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Opera World, 14 January 2015

|

| Griet Leyers |

|

|

|

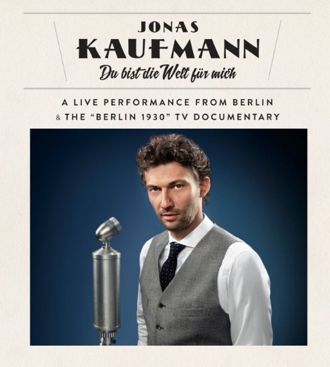

Jonas Kaufmann’s Dream Factory |

|

Why

limit these fantastic songs to an occasional encore? That is the

basic idea behind Jonas Kaufmann’s project ‘Berlin 1930.’ In a

documentary, a recital series with orchestra, and a CD ‘Du bist

die Welt für mich,’ star tenor Jonas Kaufmann pays tribute to

the forgotten and unsurpassed operetta and film music of the

Weimar Republic. Why

limit these fantastic songs to an occasional encore? That is the

basic idea behind Jonas Kaufmann’s project ‘Berlin 1930.’ In a

documentary, a recital series with orchestra, and a CD ‘Du bist

die Welt für mich,’ star tenor Jonas Kaufmann pays tribute to

the forgotten and unsurpassed operetta and film music of the

Weimar Republic.

In January 1926 the celebrated belcanto

tenor Richard Tauber becomes a superstar thanks to the song

‘Gern hab’ ich die Frauen geküsst.’ Supported by new media forms

such as radio and talkies, the hit song from Franz Lehar’s

operetta “Paganini” transforms the name Richard Tauber into a

household word overnight – simultaneously creating renewed

success for composer Franz Lehar.

Those were the golden

days for tenors. Besides Lehar, composers such as Robert Stolz,

Emmerich Kalman and Paul Abraham vied to outdo each other by

writing ever more wonderful melodies for their favorite tenors.

In spite of the eventually acidified friendship between

composers Lehar and Kalman, described by daughter Yvonne Kalman

in the documentary ‘Berlin 1930,’ the friendship, cooperation

and professional flexibility within a group of very talented

artists based in Berlin at that time is striking. For example

Kalman’s favorite tenor Hubert Marischka staged operetta

productions in which Richard Tauber starred as the lead tenor.

His brother Ernst Marischka, known as director of the Sissi

trilogy with Romy Schneider, wrote the lyrics for the worldwide

hit ‘Du bist die Welt für mich’ in the operetta ‘Der Singenden

Traum’ – which was composed and often conducted by Richard

Tauber – while tenor Joseph Schmidt sang the leading role.

Joseph Schmidt was yet another great star tenor of that period.

At the diminutive height of 1m55 he was too short for the opera

stage, but in the new media of radio and talkies, his gorgeous

voice and underdog charm turned him into a star.

Im Traum

Despite Germany’s pioneering role in

women’s rights – the Weimar Republic’s Constitution of 1919

granted suffrage to women – no one seemed to object to lyrics

like “Take her, just kiss her, that’s what women are here for”

(from “Gern hab’ ich die Frauen geküsst). This apparent

contradiction probably fits in with the joyous atmosphere of the

post-war and post-depression era. The enormous desire for

carefree entertainment and unfettered dreaming achieves yet

another dimension after the great depression of 1929. The flight

from reality is illustrated by the song ‘Im Traum’ by Robert

Stolz, rediscovered by Kaufmann in preparation for this project.

In an interview presented in a 2009 documentary, the late Martha

Eggerth, widow of star and sex symbol/tenor Jan Kiepura, reveals

how she expressed her objections to Stolz when he made her

husband sing “Blonde or brown, I love all women.” Her Jan was

supposed to love her and her alone. However, her objections do

not seem to have had any effect on Stolz and his collegues. Many

of the song lyrics cannot be considered anything other than

erotic. The suggestive text “In my dream, you’ve allowed me

everything” is juxtaposed with a beautiful and romantic (almost

naïve) melody embellished with hummed lines, which seem to come

straight out of Walt Disney’s Snow White (1937). This thinly

veiled eroticism runs like a red thread through quite a few of

the hit songs of the 1920-1930’s.

Das Lied ist

aus

In 1933, the curtain falls on the Weimar

Republic and thus comes to an end the creative heyday of Berlin.

Due to their Jewish origin, most of our main characters have

become undesirable. In 1933 superstar Richard Tauber is

assaulted by Brownshirts on the streets of Berlin and flees to

Vienna. With the annexation of Austria in 1938, he is once again

forced to leave and settles in London where he dies in 1948.

Between 1933 and 1938 composer Robert Stolz smuggles numerous

artists from Berlin to Vienna in the trunk of his car. In spite

of his heroic efforts, the lives of many of his colleagues are

irretrievably broken. Fritz Lohner-Beda, one of the star lyrics

writers, dies in 1942 in Auschwitz. Joseph Schmidt does not

manage to immigrate to the US and ends up in a refugee camp in

Switzerland where he dies in 1942 from a severe throat

infection. Paul Abraham manages to escape through Paris and

Cuba, but fails to repeat his Berlin success in New York. In

1956 he returns to his homeland, sick and psychologically

disturbed. He dies in Hamburg in 1960.

For others the

story ended less dramatically. Lehar could remain in Austria

after his Jewish wife – through direct intercession of Goebbels

– was given the status of “honorary Aryan.” Korngold, author of

‘Die Tote Stadt,’ immigrated to the US where he became one of

the greatest Hollywood composers. After the annexation of

Austria, Robert Stolz left for the US as well. Despite the

success of his concerts there, he returned to Austria in 1946.

He managed to rebuild his European career after the war and died

in West Berlin in 1975.

Respect, love and fun

“We refuse to put labels on good music” seems to be the

underlying message of this striking project. Careful research,

respect for the score and a fantastic team demonstrate that

judging music according to its operetta, film, or opera “box” is

not only completely beside the point, but also lacks any musical

foundation.

From the opening song, conductor Jochen

Rieder takes us all the way to Weimar through his ingenious

tempo changes and phrasing. His choices and timing are refined

and tasteful. His intentions are masterfully executed by the

Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, a group of people who have this

music running through their veins. Another highlight of this

production is soprano Julia Kleiter. The gorgeous legati and

extended musical phrases (of both singers) in the duet from ‘Die

Tote Stadt’ are breathtakingly beautiful. In Diwanpüppchen,

Kleiter is smart, funny and catchy.

Special and striking

is the documentary/promotional film ‘Berlin 1930’ by Thomas

Voigt and Wolfgang Wunderlich (Wunderlich Medien). It reflects

the atmosphere of the 20’s and 30’s and portrays Kaufmann’s

exciting research, taking us on a trip through German film

archives and private collections and presenting interviews with

remaining relatives of composers Kalman and Stolz.

The animal

It is (yet again) a challenge

not to drop into the superlatives pitfall while describing

Kaufmann’s contribution to this project. His technical mastery,

the perfect dose of his voice in each song, his classy phrasing

and his voice make him simply ‘hors category.’ What makes this

project unique however is that Kaufmann takes us on his personal

journey to discover the iceberg of wonderful music of which we

previously knew only the tip, including the beautiful ‘Grüss mir

mein Wien’ by Kalman for example, or the previously mentioned

‘Im Traum’ by Robert Stolz, of which the original score is

missing. ‘Das Lied der Schrenk,’ a killer aria Eduard Kunecke

wrote for the Danish tenor Helge Roswenger, is yet another great

discovery. Besides Roswenger himself, only Rudolf Schock and

Fritz Wunderlich accepted the challenge to record this beastly

difficult aria.

The story goes that the famous baritone

and pedagogue Josef Metternich with whom Kaufmann studied told

him “My lad, I will awaken the beast in you and once it’s out,

there’s no putting it back in the box.” I can only agree with

Mr. Thomas Voigt when he states that the late Josef Metternich

would have been impressed by the sound of “the beast” in his new

CD.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|