|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Classical Review, February 24, 2012 |

| By Charles T. Downey |

|

|

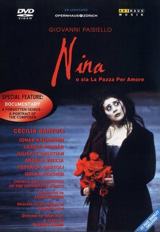

PAISIELLO Nina

|

|

|

Although

it is hard to believe now, Rossini was booed off the stage at the disastrous

opening in 1816 of his opera Il barbiere di Siviglia, its first-night

audience perturbed by the young upstart composer daring to challenge one of

the most popular Italian operas of the age, Giovanni Paisiello’s opera on

the same story, from 1782. Although

it is hard to believe now, Rossini was booed off the stage at the disastrous

opening in 1816 of his opera Il barbiere di Siviglia, its first-night

audience perturbed by the young upstart composer daring to challenge one of

the most popular Italian operas of the age, Giovanni Paisiello’s opera on

the same story, from 1782.

A composer beloved of Napoleon Bonaparte,

the novelist Stendhal, and many others in the 19th century, Paisiello has

been largely forgotten, although many of the innovative sounds of his

earlier operas were absorbed by Mozart (indeed, Paisiello’s Barbiere,

performed in Vienna in 1783, was likely an important model for Le nozze di

Figaro.)

The Italian mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli, however, has been

performing arias by Paisiello in recital and on recordings, at least since

the 1990s. In 2002, she prevailed on the Opernhaus Zürich to mount

Paisiello’s Nina, o sia La Pazza per Amore (‘Nina, or The Love-distressed

Maid). A DVD of that production duly followed in 2003 and is re-issued now

by Arthaus Musik. If you did not buy it first time around, it is well worth

a second thought.

Nina is not much more than a star vehicle for the

title character, an opera that is, essentially, one long mad scene with a

sentimentally happy ending. Nina’s marriage to her beloved Lindoro was

forbidden by her father, a Count. Lindoro flees and Nina, having lost her

senses fearing he is dead, is placed in a sanatorium. While visiting her,

the Count learns how she lives from day to day under the caring protection

of a maidservant, Susanna, and the local villagers. Moved to pity, he is

overjoyed to learn of Lindoro’s return, embraces him as his son, and

belatedly approves of his daughter’s betrothal. Nina recovers, and the

marriage is proclaimed.

Director Cesare Lievi used the second

(two-act) version of the opera made by Paisiello for his native Naples in

1790, for a Zurich production that suggested Nina’s insanity was a ploy to

change her father’s rejection of Lindoro as her would-be husband. In an

accompanying documentary on this DVD, Lievi states quite clearly that “Nina

is not crazy, she only pretends to be crazy,” hurting her father by giving

away his money to the villagers who visit and sing to her, and, more

woundingly, even appearing to no longer recognize him. Which is why Lievi

has Jonas Kaufmann’s Lindoro also play the role of the shepherd in Act I, as

he is part of the ploy.

The title role was created for a soprano, so

the top sits a little uncomfortably in Bartoli’s voice. Neither opera seria

nor opera buffa, the score has lots of cantabile melancholy arias and not as

much of the crazy coloratura more to Bartoli’s liking. Still, she gives a

very moving portrayal and sings with lyrical abandon.

If Bartoli does

not chew the scenery (well, a little), she does chew a flower prop and at

one point has an unattractive tantrum rolling on the floor. She captures

Nina’s contrasting moods – exaltation, melancholy, mania, depression – right

from her affecting entrance scene, and even interpolates another aria for

herself, Mozart’s ‘Ah, lo previdi’ (a replacement aria composed to be

inserted into another Paisiello opera, Andromeda) which is also about a love

thwarted by a tyrannical father.

Kaufmann shows here why his star

rose so quickly at the turn of the century, singing with both bravura

strength and finesse, as well as a handsome stage appearance. In the role of

the Count, the paternal bass of László Polgár provides a dignified,

stentorian presence, while Juliette Galstian is not quite able to handle the

highest parts of the role of Susanna.

Character baritone Angelo

Veccia has a witty turn as the comic servant Giorgio, both in the funny

wheezing aria (when he cannot get out the news that Lindoro has returned,

albeit not always exactly in the same time signature as the orchestra) and

the drunken aria in Act I, reassuring Nina’s father that she will recover.

Conductor Ádám Fischer has a sure hand with the band of the Zurich Opera,

using some period instruments (such as the on-stage oboe and bagpipe).

Lievi drains the color palette around Nina to gray and black (except for

the bright red flowers she carries in the entrance scena; sets and costumes

by Maurizio Balň) setting the action on a single set of Strindbergian

stringency with bare walls and a single window.

He adds many pleasing

touches to the staging, as when toward the end of Act I, the obbligato oboe

player, Bernhard Heinrichs, performs on stage with Bartoli in a lyrical

duet, like one of the birds who, she sings at one point, always respond to

her laments. The shepherd, here played by Lindoro, is accompanied in his

simple song by the rustic zampogna (medieval bagpipe), played here with folk

flavor by Michael Reid.

Star vehicle though Nina may be, it was a

mistake to film Bartoli in so many close-ups, which are not always

flattering. Shots of the star during the Overture show her staring up

reverently, like the patron saint of Paisiello. Which may be true, but they

still distract

from the music. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|